A sea otter floating in kelp. Shared under a creative commons license.

The coastline hums with a flurry of sea otters weaving in and out of waves, darting around each other, and plucking away at prey. When looking across a lively seascape like this, dense in tangled rafts of otters and kelp forests alike, it is hard to picture them missing.

But, when the fur trade took off in the 19th century, coastlines along the Pacific quieted as sea otters almost completely disappeared.

A healthy kelp forest (top picture) needs sea otters to thrive. Shared under creative commons license.

Without them, kelp forests can become dominated by urchins, transitioning once healthy kelp forests to urchin barrens. Photos shared under a creative commons license.

Little did people know then, but sea otters help balance these ecosystems with their voracious appetites. Soon after their near-extinction, the otters’ prey species, now unchecked, blossomed. Sea urchins quickly ate their fill of kelp, nearly decimating this essential underwater habitat. Many species lost their homes and food sources.

Humans are just as much a part of this ecosystem as any other species, with their own dynamic relationships with sea otters, shellfish, and the ocean.

These relationships are especially maintained by the Indigenous Peoples who have lived along the Pacific Coast since time immemorial.

The Coastal Voices Project — a collaboration led by two of the Cross-Pacific Indigenous Aquaculture steering committee members, Anne Salomon and Kii’iljuus Barbara Wilson — describes some of the complex relations that Indigenous communities have with otters. Examples of these relationships include utilizing their furs for ceremony and survival or selectively hunting them to steward a balanced ecosystem.

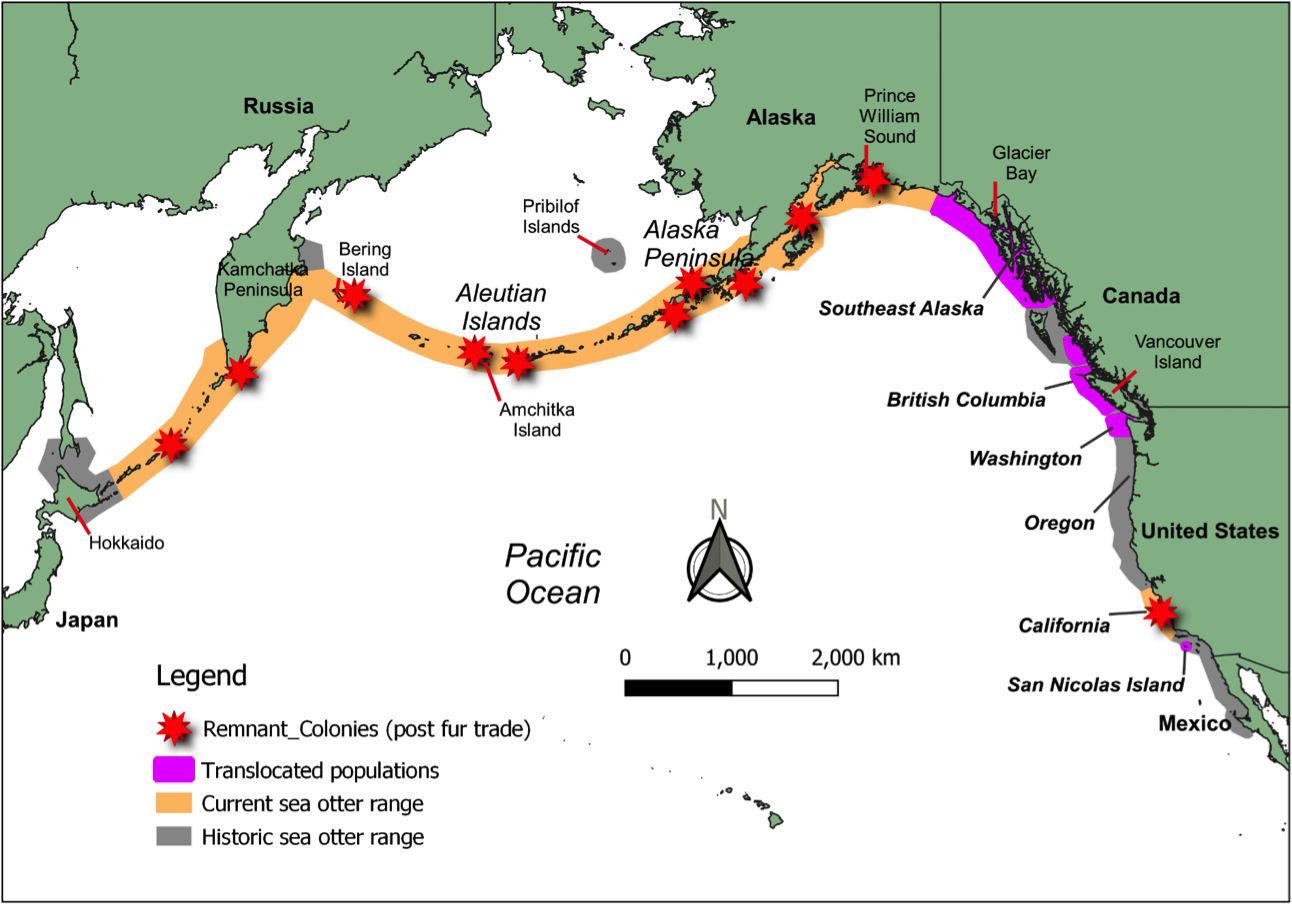

Over the last 80 years, people have tried to restore sea otters throughout the West Coast, from Alaska all the way to California. By translocating a few otters from healthy populations to areas where they once lived, people have brought otters back to many locations. While there was an early period of uncertainty as ecosystems rebalanced, populations of otters now thrive in many places along the West Coast of North America.

Map of the North Pacific showing historical and current sea otter range, the latter including translocated populations. Map courtesy of the Elakha Alliance’s Ecological Feasibility Study.

Sea Otters and Aquaculture

While successful reintroductions of otters are considered large-scale ecological wins, the social and cultural dimensions of the reintroductions have not been appreciated, and as a result, not prioritized. Sea otter reintroductions have largely been orchestrated by government agencies, rather than co-developed with Tribal Nations, consequently threatening many traditional aquaculture practices and shellfish harvests of Native American and First Nations communities.

In Alaska, sea otter populations flourished upon reintroduction. In the initial stages, otters in Alaska devoured populations of abalone, crabs, and other culturally important species. Sea otters can consume over 25% of their body weight every day to fuel their metabolism and keep their bodies warm. Their insatiable appetite for shellfish initially hurt subsistence and traditional harvesters.

A sea otter feasting on a clam. Shared under a creative commons license.

Over time, Alaskan ecosystems became more balanced as selective hunting of otters and collaborative management among Alaska Native communities and the government was implemented.

Under an exemption of the Marine Mammal Protection Act, Alaska Natives are able to continue their right to traditionally and selectively harvest otters.

With this exemption, communities can better control otter and shellfish populations while also reestablishing a cultural connection to otters through the revitalization of tanneries and the use of otter pelts for handicrafts. More recently, local residents to Southeast Alaska have noted that the sustainable harvest of reintroduced otters has resulted in rebounded populations of shellfish such as abalone, chitons, urchins and sea cucumbers, rebalancing the ecosystem at large.

In British Columbia, experiences with sea otter reintroductions are quite complex and differ from what was experienced in Alaska. During their doctoral research at the University of British Columbia, Jordan Levine and colleagues found that the opinions on sea otter reintroductions varied within First Nations communities on the British Columbia coastline. When speaking with men and women in coastal communities, their research found that women felt the greatest losses from sea otter reintroductions due to their role as the primary shellfish harvesters. While some First Nations men harvest shellfish, their primary role is fishing, where the impacts of sea otters have been known to benefit certain commercially valuable fish populations, increasing the total catch for fishers interviewed.

A Collaborative Approach to Restoring Sea Otters

The three of us — Olivia, Isabel and Danny — entered into our master’s program at the University of Washington’s School of Marine and Environmental Affairs with the goal of engaging in work that supports Indigenous resurgence and sovereignty. We hoped to better understand research methodologies that foster relationship building and expand beyond dominant, Western scientific approaches to environmental management. With these goals in mind, we began a collaborative capstone partnership with the Elakha Alliance in early 2022, working to restore otters to the Oregon coast.

A sea otter feasting on a clam. Shared under a creative commons license.

Elakha is the Chinook trading language word for sea otter and represents a long history Indigenous Peoples have held with sea otters in what is now Oregon. Sea otters were hunted for their fur along the western Pacific coastline during the maritime fur trade, and by the early 1900’s they were considered locally extinct in Oregon. Formed in 2018 by Tribal, nonprofit, and conservation leaders, the Elakha Alliance hopes to restore the ecological and cultural connections among otters and coastal communities.The Alliance seeks to evaluate how the reintroductions of sea otters to Oregon’s coastal ecosystems have the ability to restore and revitalize a culturally important species.

Tribal leadership on the Elakha Alliance’s board helps to ensure that Indigenous perspectives are central to the effort to return sea otters to Oregon. As a member of both the Elakha Board and the Confederated Tribe of Siletz Indians, Peter Hatch expresses their ancestral kinship relationship with sea otters and ocean abundance:

“Since the beginning of time, when our newly-created peoples’ footprints first marked the sands, we coexisted with Elakha. The stories of our Ancestors instruct us to recognize sea otters as one of our respected kin, our cousins as it were, and that preserving that kinship- and all our relationships to the natural world- would help us forever enjoy the bounty and abundance that the ocean has to offer for our sustenance and our prosperity.”

In our capstone work, we are interviewing Tribal members, government officials, and scientists along the Pacific coasts in hopes of providing useful frameworks that highlight opportunities for Indigenous sovereignty and co-management in sea otter reintroductions. We look forward to ongoing collaborations that support community-driven reintroduction efforts, such as the work with the Elakha Alliance, that prioritize Indigenous community needs and avoid harm to Indigenous food sovereignty and resurgence.

To learn more about the Elakha Alliance and the cultural connection that coastal Oregon Tribes share with sea otters, watch this beautiful video

About the authors: Olivia Horwedel, Isabel Jamerson, and Danny Kosiba are master’s students at the University of Washington’s School of Marine and Environmental Affairs. Their community-partnered research emphasizes Indigenous resurgence and sovereignty in marine management.

Olivia Horwedel is also the current Communications Fellow for the Cross-Pacific Indigenous Aquaculture Collaborative Network.