Standing in a circle on the beach, we set our intentions and offer accounts of our connections to the land and sea. Getting started for a day of clam garden restoration involves nurturing our relationships to each other as much as moving rocks, raking sea lettuce, and aerating the beach.

The principle of restoring relationships as enacted on the shores of Russell Island in the Gulf Islands of British Columbia, Canada is echoed in the gathering at Heʻeia, Oʻahu, Hawaiʻi as we prepare to rebuild a stretch of rock wall in a recently cleared section of the fishpond.

Cross-Pacific gathering sets out to work on the Heʻeia Fish Pond

Northwest coastal Indigenous clam gardens and Native Hawaiian fishponds (loko iʻa) are time-tested mariculture systems that bring together our community of practice, composed of stewards, knowledge holders, elders, students, educators, scientists, outreach staff, and community and tribal leaders. These diverse systems have been honed over thousands of years with the purpose to create integrated and sustainable habitats for producing customary foods, as well as spaces that give context to spiritual, social and family connections, and cultural and ethical practices. Other coastal system types under the umbrella of ‘cultural ecosystems’ include stone fish traps, salmon fish weirs, estuarine root gardens, Garry oak camas prairies, herring spawn on kelp or branches, loʻi kalo or taro patches, hanai koʻa or the practice of feeding fishing grounds and many other examples of Indigenous management systems.

Russell Island clam garden

All are cultural ecosystems that depend on people to steward them. They are adaptive, rooted in cultural protocols and traditional ecological knowledge, reflecting the biological and cultural diversity of coastal peoples, and shaping the relationships between people and coastal environments in the Pacific. The slope of the beach, the biodiversity of fishes, the attenuation of waves … these are also cultural modifications. The rock at the base of the wall —the niho stone— or the shell hash in the upper tidal zone of the clam garden are physical manifestations of intentional and collective cultural work to produce foods and manage the marine environment.

Restoring traditional Indigenous aquaculture systems such as clam/sea gardens and loko iʻa or fishponds is also about re-storying our cultural-ecological relationships, that is: bringing forth narratives, songs, prayers, testimonies of people that are written in the biology, geology and hydrology of the nearshore.

Offering to set intentions for a day of fishpond restoration. Photo credit Scott Kanda, courtesy KUA

So, what is a clam garden? What is a fishpond?

Clam gardens, or “sea gardens” as they are becoming recognized, are cultivated nearshore areas that are tended to create optimal habitat for coastal species like butter clams, native littlenecks, sea cucumbers, urchins and other culturally-important intertidal foods.

Swinomish community members work together to restore the rock wall of a clam garden. Photo credit: Courtney Greiner

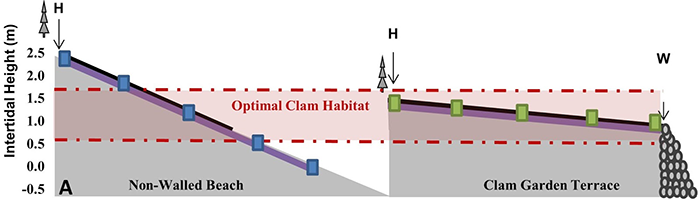

A common feature of this type of system is terracing created by clearing and stacking rocks to form walls, change the beach slope, and alter water temperature and hydrology. In some places, marine algae is removed and beach gravel is aerated. There are many diverse techniques throughout the Northwest Coast. Modifying the beach in this way increases the availability of productive clam habitat (namely, favorable sediment and nutrients) and increases the abundance and size of clams, among other desired outcomes. Oral histories and ethnographic records document the deeply historic importance of tending clams and intertidal areas. Radio-carbon dating tells us that these ancient technologies extend back at least 3,500 years.

In comparison to non-walled beaches (A), those with clam garden terraces (B) increase the amount of optimal clam habitat. Source: Groesbeck et al. (2014) PLOS One

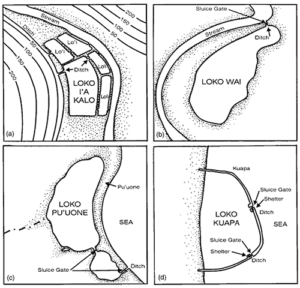

Different types of traditional fish ponds. Costa-Pierce, B. A. (Ed.). (2008). Ecological aquaculture: the evolution of the blue revolution. John Wiley & Sons.

Loko Iʻa are unique aquaculture systems throughout Hawaiʻi, rooted in cultural and environmental knowledge of ahupuaʻa (traditional land stewardship framework). Like clam gardens, stewards of loko iʻa (or traditional Hawaiian fishponds) apply iterative observation-based Indigenous science to optimize habitat for desired animals and plants (like taro), and are maintained through relationships between people and the land and water.

There are different kinds of fishponds that have been adapted for local places and needs, and each function to provide sustainable foods nurtured through community stewardship. By some counts, there are nearly 500 Native Hawaiian fishponds throughout the islands in various conditions, many that are currently being restored by a network of local communities. Fishponds are designed to attract fish, manage water and nutrient flows, and provide access to culturally-important local foods often through the use of rock walls, sluice gates to control tidal and flood waters, and biological techniques such as removal of invasive plants and fish.

The access to place-based foods is especially critical in Hawaiʻi where social and ecological resilience is partly dependent on food security and food sovereignty. Loko iʻa as an ahupuaʻa based food system work with the natural processes of the watershed and ocean, and nurture a vision of restoration centering Hawaiian cultural and spiritual protocols, leadership, and community self-determination.

Throughout the Pacific, Indigenous people have not just been passively living with the land and ocean, but they/we actively maintain them for food, cultural and spiritual uses, and trade. They/we have designed innovative techniques based on ancestral knowledge to manage local ecosystems to enhance productivity and care for important resources. These innovations hold lessons for adaptations to future changing environments.

In this space, we celebrate the knowledge holders, ancestors and caretakers who have kept these traditions alive and who are working hard to reawaken and strengthen them.

Clam garden