For the last meeting of the week, participants gather in person and over Zoom wearing the handmade paul hetaf, a common hand adornment used in ceremonies in Lamotrek, Federated States of Micronesia. Photo by Reid Endress.

Sm-lack. Sm-lack. Sm-lack.

The sound of a dozen ʻiwa birds (Hawaiian for Great Frigatebirds/Fregata minor) handmade from coconut leaves set a mesmerizing beat. Their angular fiber wings flapping on the fingers of the wearers.

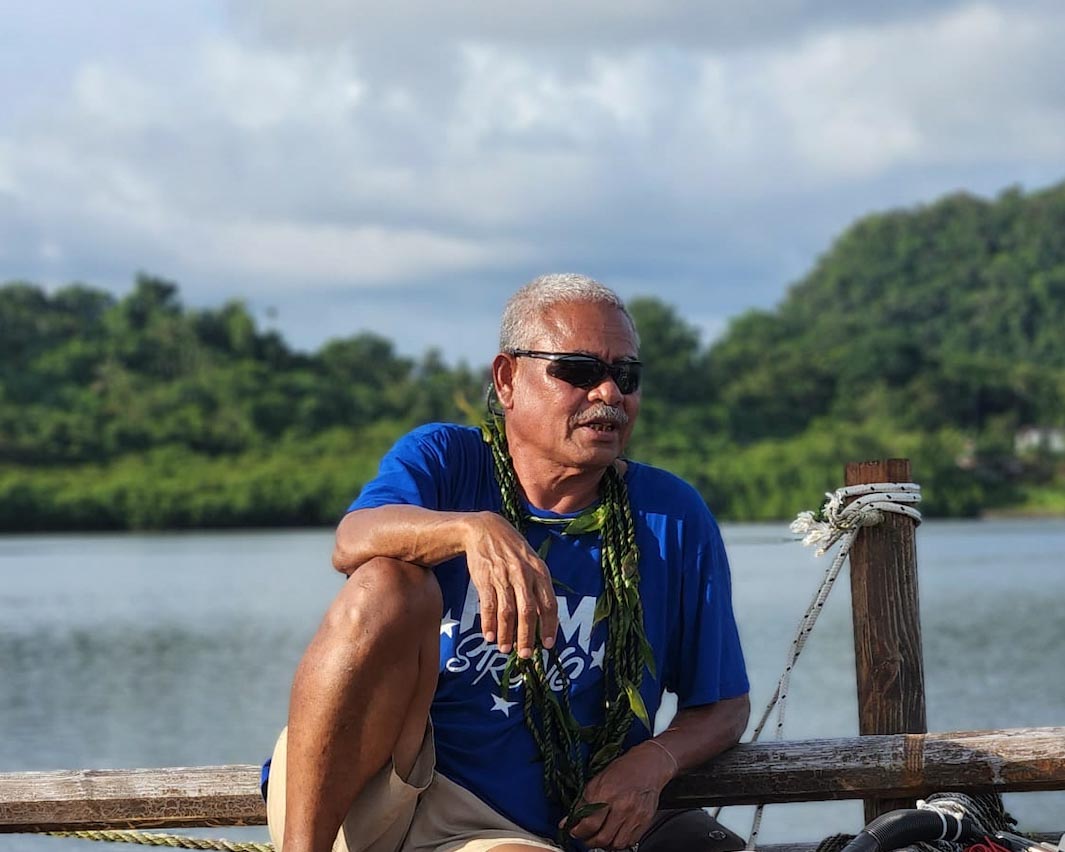

“We always use this frigatebird to welcome everybody,” says Uncle Larry Raigetal, a Pwo navigator from Lamotrek (a coral atoll within Yap, a group of islands in the Federated States of Micronesia). He’s also a nephew to Mau Piailug, who taught traditional navigation to Nainoa Thompson, a founder and current CEO of the Polynesian Voyaging Society.

Participants Aunty Barb Wilson (left) and Darienne Dey (right) make paul hetaf and lei (a Polynesian garland of flowers or leaves) from coconut and ti leaves everyone harvested earlier in the day. Photo by Momi Afelin.

Host Ann Singeo and Hawaiian loko iʻa (fishpond) practitioners explore Palau’s first known beng to see how to begin restoration. Photo by Reid Endress.

Uncle Larry Raigetal (left), Keliʻi Kotubetey (middle), and Ann Singeo (right) draw in the sand how the beng would have looked and functioned. Photo by Momi Afelin

In Lamotrekese, these hand adornments are called paul hetaf. We made them the night before specifically in preparation for today’s meeting.

Indigenous practitioners from Hawaiʻi, Federated States of Micronesia, and Haida Gwaii (in what is now British Columbia, Canada) have gathered in Palau at the end of July for a 5-day knowledge exchange.

Together, the dozen participants represent traditional celestial navigation, the Cross-Pacific Indigenous Aquaculture Collaborative, and the host Palauan organization Ebiil Society, which manages natural resources and teaches environmental education using local Indigenous knowledge.

We had spent our time together outplanting giant clams into the ocean, assessing how to restore Palau’s first beng (fish weir), visiting traditional milkfish ponds, and studying the stars with Uncle Larry.

Now, on the last day, Uncle Larry begins the meeting by opening our ocean connection with an ancient seafaring chant called Sumetau.

The paul hetaf hum in the background as he chants.

His words are in Kkapesen neimatau. The Talk of Sea. Some of the words he admits he does not speak.

“I have learned chants that have language that is foreign. And I have asked my teachers, ‘What does this mean?’”

“The best answer I could get is don’t worry about it. It’s not our language. It’s the language of the ocean. The ocean hears it better when you say it that way.”

And so, he speaks in this foreign language, just as those before him have done for thousands of years.

The mana (Hawaiian for energy/supernatural or divine power) in the room is tangible and infectious, radiating through Zoom and across thousands of miles of ocean to those who could not join in person.

The words captivatingly lead us through what Uncle Larry previously described as the seven layers of the ocean. It begins with the Ocean of Reefs.

“A place of certainties. Of confidence. We know where we are,” he explains. “Then we go out into the challenges.”

The Ocean of Thirst, the Ocean of Hunger, and the Oceans of Temptations must be crossed before ending at the Ocean of Breadfruit. “That that we all wanted.”

Breadfruit (ʻulu in Hawaiian) is a culturally important starch eaten throughout Oceania. But today it takes on an even deeper meaning. Just the day before, we had been removing barnacles from the hull of Alingano Maisu—a waʻa kaulua (Hawaiian for a traditional double-hulled sailing canoe) made on the Big Island of Hawaiʻi and gifted to Mau and his family.

Sesario Sewralur, Mau’s son, explained its name.

“To share the beauty of the fallen breadfruit,” he says. Per Polynesian custom, one cannot take fruit from a neighbor while it is still on their tree. However, once the fruit is on the ground, it is free for the community.

Sesario reminded us that when Mau shared his navigational knowledge with Hawaiians, he had broken an ancient cultural prohibition against giving Kkapesen neimatau to outsiders. But he felt it was the right course because it was about survival.

Sesario Sewralur, Mau’s son, captains Alingano Maisu while teaching the importance of its name. Photo by Kimeona Kane.

Participants of the knowledge exchange (from left to right) Paula Moehlenkamp, Amanda Millin, and Momi Afelin scrape barnacles off the hulls of Alingano Maisu. Photo by Kimeona Kane.

Alingano Maisu is a waʻa kaulua (Hawaiian for a traditional double-hulled sailing canoe) made on the Big Island of Hawaiʻi and gifted to Mau and his family. Photo by Kimeona Kane.

Later that night, the group sat talking story, and we all agreed—we were in Palau sharing knowledge across cultures again for survival. Cultivating habitats to grow seafood, food sovereignty, navigation, boatbuilding, and sailing are each a breadfruit ready to be shared.

Uncle Larry has switched into English, and my mind is pulled back to his words.

“We seek permission from the ghosts and the spirits of the ocean because we believe it’s them that controls all of this. I’m pretty sure if we don’t listen to them, they will not listen to us.”

Cross-Pacific knowledge exchange participants join Ann Singeo, executive director of Ebiil Society, to learn more about beng, a traditional mariculture system of Palau. Photo by Kimeona Kane.

Participant Ikaika Rogerson (left) and MJ Aunu (right, of the host organization Ebiil Society) prepare to outplant giant clams into the Pacific Ocean. Photo by Amanda Millin.

Of course, Uncle Larry is not alone in these beliefs. Such worldviews are at the epicenter of Indigenous and traditional knowledge systems.

In the book Hawaiki Rising (a true story about the people, practices, and events that led to the birth of Hōkūleʻa, the Polynesian Voyaging Society, and the Hawaiian Renaissance), Sam Low elaborates on the sacredness of ancestral knowledge, which endures with technical observations and is sanctioned by spiritual force to heal, to feed people, and connect community.

This weaving together of community is also a key lesson from Nainoa’s dad, Pinky Thompson:

“You need to define your community, and community is never about what separates you from each other—your race or your culture—it’s about what binds you together.”

In a small but important way, the Palau knowledge exchange continued this process.

Intentional space was created, allowing a group of knowledge holders, including Indigenous practitioners and community leaders, to come together as a community and lay out a vision for a unified Pacific.

“When we lose our knowledge of the land and the ocean, then we lose the health of those places,” says Ebiil Society’s founder and taro farmer, Ann Singeo. “At the root of this is the shared struggle of maintaining our own identity and maintaining the knowledge that has sustained our people for thousands of years.”

In effort to help prevent this from happening, the group envisions an international grassroots movement that continues creating spaces for Pacific Indigenous practitioners to work and learn alongside each other in the ocean and in the ‘āina (land, earth/literally that which feeds). In the process, the movement scales up from place-based communities; bridging isolation, building pilina (Hawaiian for trust/relationships), and ultimately establishing a common Pacific voice to address climate change, ocean health, and social equity.

And as one participant, Kii’iljuus—aka Aunty Barb Wilson, a steering committee member of the Cross Pacific Indigenous Aquaculture Collaborative and matriarch of the St’awaas Xaaydagaay (Cumshewa Eagle Clan) in Haida Gwaii—elaborates, “[Our community] is about more than just the Pacific. But it’s a good place to start.”

Amanda Millin is a Cross-Pacific Indigenous Aquaculture Collaborative member.